Cramér’s V is a number between 0 and 1 that indicates how strongly two categorical variables are associated. If we'd like to know if 2 categorical variables are associated, our first option is the chi-square independence test. A p-value close to zero means that our variables are very unlikely to be completely unassociated in some population. However, this does not mean the variables are strongly associated; a weak association in a large sample size may also result in p = 0.000.

Cramér’s V - Formula

A measure that does indicate the strength of the association is Cramér’s V, defined as

$$\phi_c = \sqrt{\frac{\chi^2}{N(k - 1)}}$$

where

- \(\phi_c\) denotes Cramér’s V;\(\phi\) is the Greek letter “phi” and refers to the “phi coefficient”, a special case of Cramér’s V which we'll discuss later.

- \(\chi^2\) is the Pearson chi-square statistic from the aforementioned test;

- \(N\) is the sample size involved in the test and

- \(k\) is the lesser number of categories of either variable.

Cramér’s V - Examples

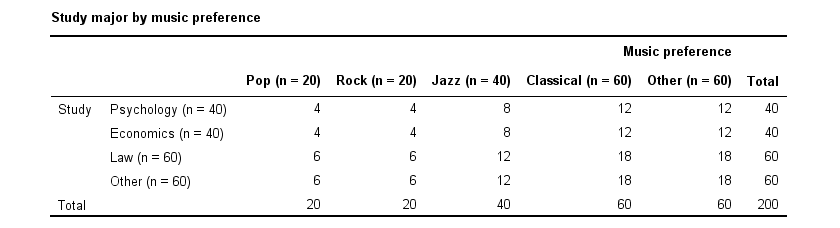

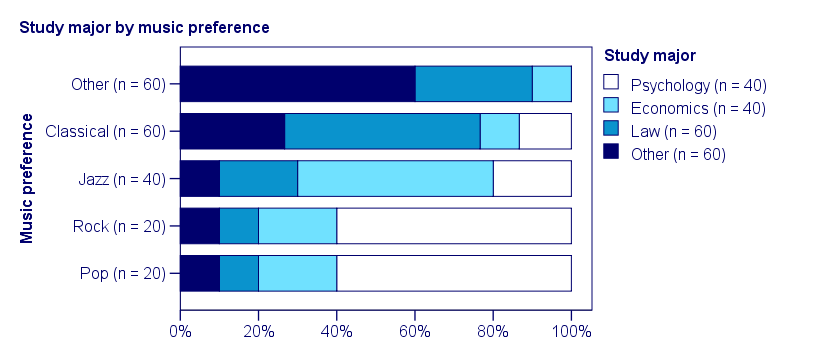

A scientist wants to know if music preference is related to study major. He asks 200 students, resulting in the contingency table shown below.

These raw frequencies are just what we need for all sort of computations but they don't show much of a pattern. The association -if any- between the variables is easier to see if we inspect row percentages instead of raw frequencies. Things become even clearer if we visualize our percentages in stacked bar charts.

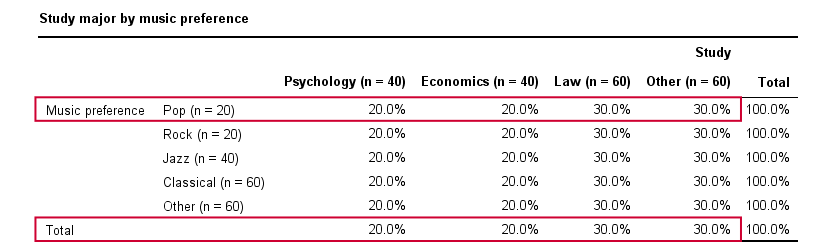

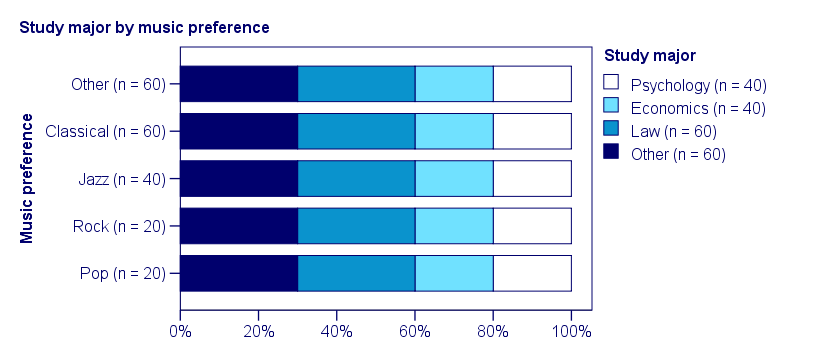

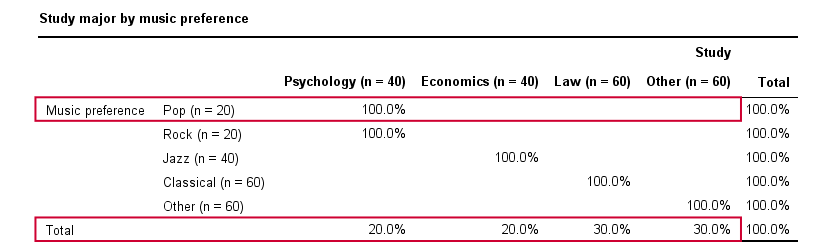

Cramér’s V - Independence

In our first example, the variables are perfectly independent: \(\chi^2\) = 0. According to our formula, chi-square = 0 implies that Cramér’s V = 0. This means that music preference “does not say anything” about study major. The associated table and chart make this clear.

Note that the frequency distribution of study major is identical in each music preference group. If we'd like to predict somebody’s study major, knowing his music preference does not help us the least little bit. Our best guess is always law or “other”.

Cramér’s V - Moderate Association

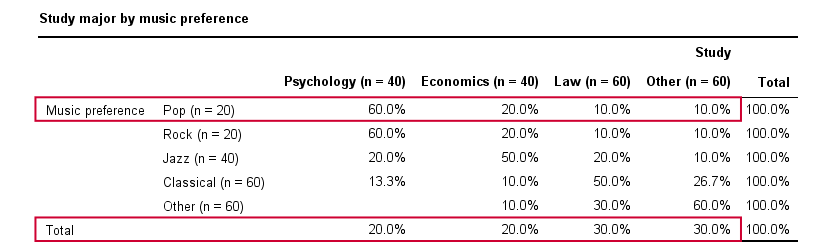

A second sample of 200 students show a different pattern. The row percentages are shown below.

This table shows quite some association between music preference and study major: the frequency distributions of studies are different for music preference groups. For instance, 60% of all students who prefer pop music study psychology. Those who prefer classical music mostly study law. The chart below visualizes our table.

Note that music preference says quite a bit about study major: knowing the former helps a lot in predicting the latter. For these data

- \(\chi^2 \approx\) 113;For calculating this chi-square value, see either Chi-Square Independence Test - Quick Introduction or SPSS Chi-Square Independence Test.

- our sample size N = 200 and

- we've variables with 4 and 5 categories so k = (4 -1) = 3.

It follows that

$$\phi_c = \sqrt{\frac{113}{200(3)}} = 0.43.$$

which is substantial but not super high since Cramér’s V has a maximum value of 1.

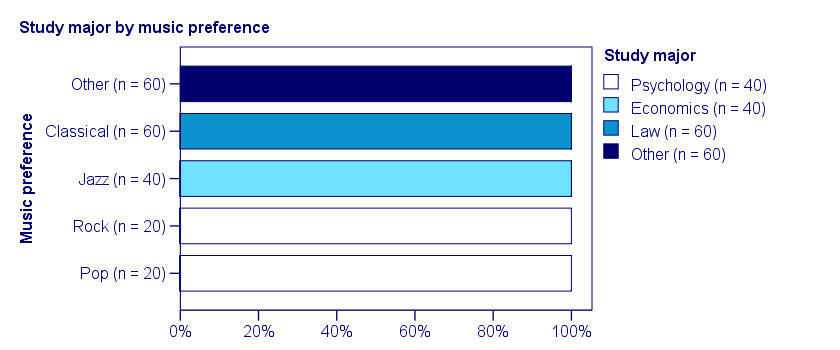

Cramér’s V - Perfect Association

In a third -and last- sample of students, music preference and study major are perfectly associated. The table and chart below show the row percentages.

If we know a student’s music preference, we know his study major with certainty. This implies that our variables are perfectly associated. Do notice, however, that it doesn't work the other way around: we can't tell with certainty someone’s music preference from his study major but this is not necessary for perfect association: \(\chi^2\) = 600 so

$$\phi_c = \sqrt{\frac{600}{200(3)}} = 1,$$

which is the very highest possible value for Cramér’s V.

Alternative Measures

- An alternative association measure for two nominal variables is the contingency coefficient. However, it's better avoided since its maximum value depends on the dimensions of the contingency table involved.3,4

- For two ordinal variables, a Spearman correlation or Kendall’s tau are preferable over Cramér’s V.

- For two metric variables, a Pearson correlation is the preferred measure.

- If both variables are dichotomous (resulting in a 2 by 2 table) use a phi coefficient, which is simply a Pearson correlation computed on dichotomous variables.

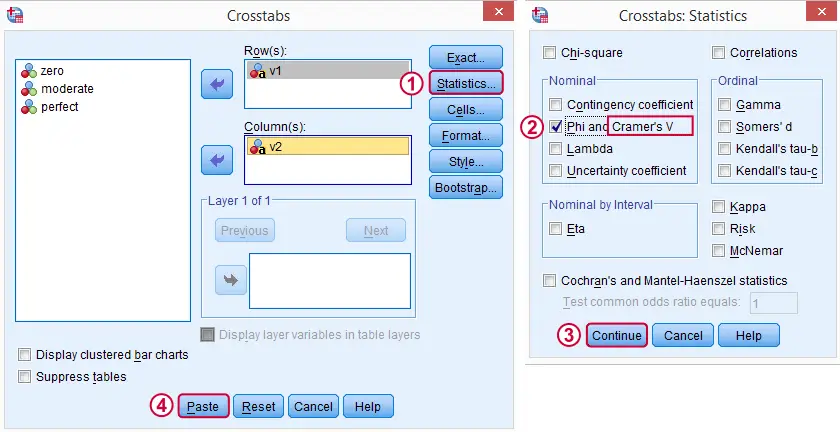

Cramér’s V - SPSS

In SPSS, Cramér’s V is available from

. Next, fill out the dialog as shown below.

. Next, fill out the dialog as shown below.

Warning: for tables larger than 2 by 2, SPSS returns nonsensical values for phi without throwing any warning or error. These are often > 1, which isn't even possible for Pearson correlations. Oddly, you can't request Cramér’s V without getting these crazy phi values.

Final Notes

Cramér’s V is also known as Cramér’s phi (coefficient)5. It is an extension of the aforementioned phi coefficient for tables larger than 2 by 2, hence its notation as \(\phi_c\). It's been suggested that its been replaced by “V” because old computers couldn't print the letter \(\phi\).3

Thank you for reading.

References

- Van den Brink, W.P. & Koele, P. (2002). Statistiek, deel 3 [Statistics, part 3]. Amsterdam: Boom.

- Field, A. (2013). Discovering Statistics with IBM SPSS Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Howell, D.C. (2002). Statistical Methods for Psychology (5th ed.). Pacific Grove CA: Duxbury.

- Slotboom, A. (1987). Statistiek in woorden [Statistics in words]. Groningen: Wolters-Noordhoff.

- Sheskin, D. (2011). Handbook of Parametric and Nonparametric Statistical Procedures. Boca Raton, FL: Chapman & Hall/CRC.

SPSS TUTORIALS

SPSS TUTORIALS

THIS TUTORIAL HAS 8 COMMENTS:

By Jon Peck on December 9th, 2016

On the phi statistic with non 2x2 tables, as the What's This and Algorithms text point out,

For a 2x2 table only, phi is equal to the Pearson correlation coefficient so that the sign of phi matches that of the correlation coefficients.

But the significance level is still appropriate (and the same as V). In the 2x2 case, phi and V are the same.

Second point, you say, in the perfect example, that we can tell the major perfectly from the music preference but not the other way around. Since this table is diagonal, why doesn't it work both ways?

By Ruben Geert van den Berg on December 9th, 2016

Hi Jon, thanks for your feedback! IMHO, SPSS should simply refuse to calculate phi if the table is not 2x2 and throw an error or warning that phi can't be computed. I believe this actually happens for some other statistics. To me, this seems preferable over relying on the user knowing when to (not) ignore the nonsensical phi values. You don't want less knowledgeable users to include SPSS phi values of 1.41 in their reports, right?

Second point, we've a 4x5 table. Half of the psychology students prefer Rock and half prefer Pop so we can't tell for sure from their study. However, all Rock and Pop lovers do study psychology.

By Jon Peck on December 9th, 2016

Ah, I see about the table. The way it is formatted, I missed the first row altogether.

As for phi, it is still defined for a non 2x2 table as sqrt(chi-squared/N), but since it equals V for 2x2, I guess there really isn't any point to ever showing it.

By Abdulrahman on December 14th, 2016

Thank you veey much. It clear :) and waaw

By Dr Frank Thomas on May 15th, 2017

Hi,

A well-written, clear text.

I would just remark that in the case of yes/no tems lists which you often find in survey or marketing research Cramer's V values the nonpresence the same as a presence. If you have a long list of 0/1 items (which household items do you own) and respondents only own a few of them ( which oftne happens) you get distortion.