- Logistic Regression Equation

- Logistic Regression Example Curves

- Logistic Regression - B-Coefficients

- Logistic Regression - Effect Size

- Logistic Regression Assumptions

Logistic regression is a technique for predicting a

dichotomous outcome variable from 1+ predictors.

Example: how likely are people to die before 2020, given their age in 2015? Note that “die” is a dichotomous variable because it has only 2 possible outcomes (yes or no).

This analysis is also known as binary logistic regression or simply “logistic regression”. A related technique is multinomial logistic regression which predicts outcome variables with 3+ categories.

Logistic Regression - Simple Example

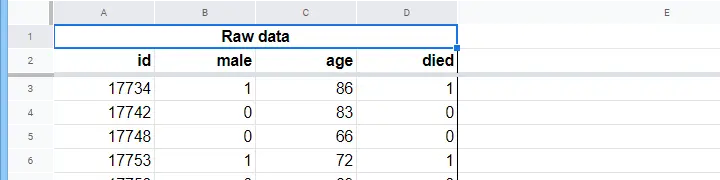

A nursing home has data on N = 284 clients’ sex, age on 1 January 2015 and whether the client passed away before 1 January 2020. The raw data are in this Googlesheet, partly shown below.

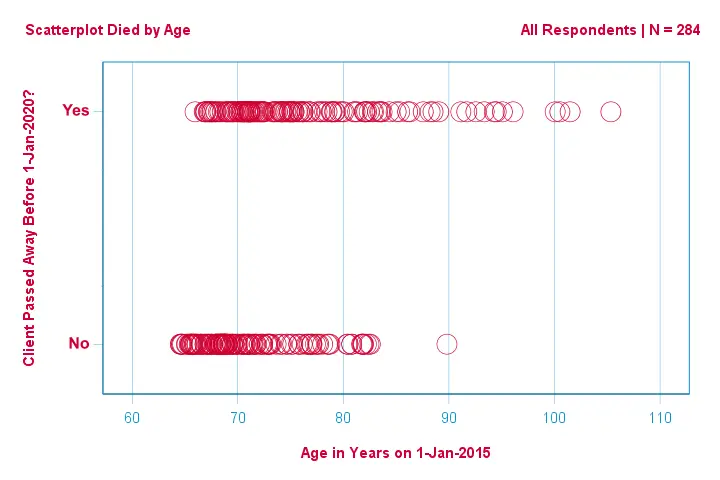

Let's first just focus on age: can we predict death before 2020 from age in 2015? And -if so- precisely how? And to what extent? A good first step is inspecting a scatterplot like the one shown below.

A few things we see in this scatterplot are that

- all but one client over 83 years of age died within the next 5 years;

- the standard deviation of age is much larger for clients who died than for clients who survived;

- age has a considerable positive skewness, especially for the clients who died.

But how can we predict whether a client died, given his age? We'll do just that by fitting a logistic curve.

Simple Logistic Regression Equation

Simple logistic regression computes the probability of some outcome given a single predictor variable as

$$P(Y_i) = \frac{1}{1 + e^{\,-\,(b_0\,+\,b_1X_{1i})}}$$

where

- \(P(Y_i)\) is the predicted probability that \(Y\) is true for case \(i\);

- \(e\) is a mathematical constant of roughly 2.72;

- \(b_0\) is a constant estimated from the data;

- \(b_1\) is a b-coefficient estimated from the data;

- \(X_i\) is the observed score on variable \(X\) for case \(i\).

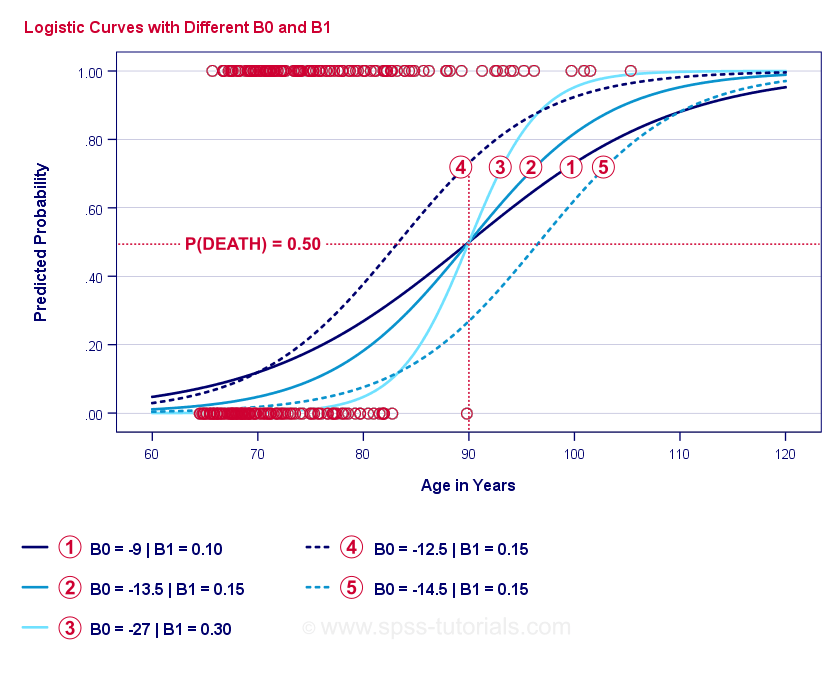

The very essence of logistic regression is estimating \(b_0\) and \(b_1\). These 2 numbers allow us to compute the probability of a client dying given any observed age. We'll illustrate this with some example curves that we added to the previous scatterplot.

Logistic Regression Example Curves

If you take a minute to compare these curves, you may see the following:

- \(b_0\) determines the horizontal position of the curves: as \(b_0\) increases, the curves shift towards the left but their steepnesses are unaffected. This is seen for curves

,

,  and

and  . Note that \(b_0\) is different but \(b_1\) is equal for these curves.

. Note that \(b_0\) is different but \(b_1\) is equal for these curves. - As \(b_0\) increases, predicted probabilities increase as well: given age = 90 years, curve

predicts a roughly 0.75 probability of dying. Curves

predicts a roughly 0.75 probability of dying. Curves  and

and  predict roughly 0.50 and 0.25 probabilities of dying for a 90-year old client.

predict roughly 0.50 and 0.25 probabilities of dying for a 90-year old client. - \(b_1\) determines the steepness of the curves: if \(b_1\) > 0, the probability of dying increases with increasing age. This relation becomes stronger as \(b_1\) becomes larger. Curves

,

,  and

and  illustrate this point: as \(b_1\) becomes larger, the curves get steeper so the probability of dying increases faster with increasing age.

illustrate this point: as \(b_1\) becomes larger, the curves get steeper so the probability of dying increases faster with increasing age.

For now, we've one question left: how do we find the “best” \(b_0\) and \(b_1\)?

Logistic Regression - Log Likelihood

For each respondent, a logistic regression model estimates the probability that some event \(Y_i\) occurred. Obviously, these probabilities should be high if the event actually occurred and reversely. One way to summarize how well some model performs for all respondents is the log-likelihood \(LL\):

$$LL = \sum_{i = 1}^N Y_i \cdot ln(P(Y_i)) + (1 - Y_i) \cdot ln(1 - P(Y_i))$$

where

- \(Y_i\) is 1 if the event occurred and 0 if it didn't;

- \(ln\) denotes the natural logarithm: to what power must you raise \(e\) to obtain a given number?

\(LL\) is a goodness-of-fit measure: everything else equal, a logistic regression model fits the data better insofar as \(LL\) is larger. Somewhat confusingly, \(LL\) is always negative. So

we want to find the \(b_0\) and \(b_1\) for which

\(LL\) is as close to zero as possible.

Maximum Likelihood Estimation

In contrast to linear regression, logistic regression can't readily compute the optimal values for \(b_0\) and \(b_1\). Instead, we need to try different numbers until \(LL\) does not increase any further. Each such attempt is known as an iteration. The process of finding optimal values through such iterations is known as maximum likelihood estimation.

So that's basically how statistical software -such as SPSS, Stata or SAS- obtain logistic regression results. Fortunately, they're amazingly good at it. But instead of reporting \(LL\), these packages report \(-2LL\).

\(-2LL\) is a “badness-of-fit” measure which follows a

chi-square-distribution.

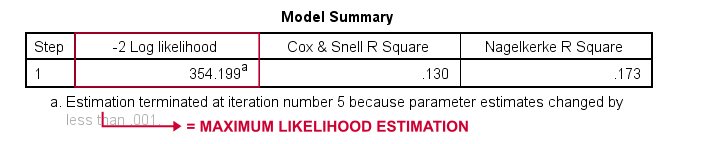

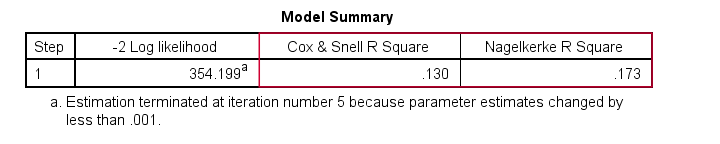

This makes \(-2LL\) useful for comparing different models as we'll see shortly. \(-2LL\) is denoted as -2 Log likelihood in the output shown below.

The footnote here tells us that the maximum likelihood estimation needed only 5 iterations for finding the optimal b-coefficients \(b_0\) and \(b_1\). So let's look into those now.

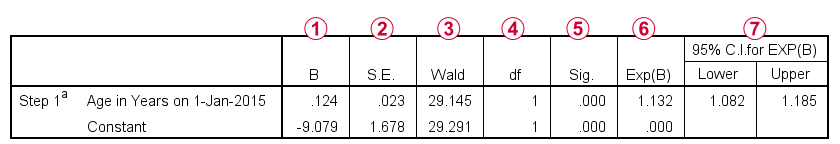

Logistic Regression - B-Coefficients

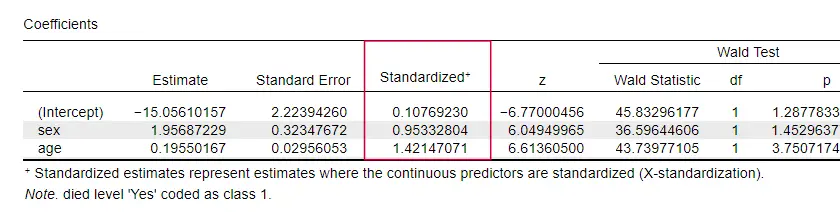

The most important output for any logistic regression analysis are the b-coefficients. The figure below shows them for our example data.

Before going into details, this output briefly shows

the b-coefficients that make up our model;

the b-coefficients that make up our model;

the standard errors for these b-coefficients;

the standard errors for these b-coefficients;

the Wald statistic -computed as \((\frac{B}{SE})^2\)- which follows a chi-square distribution;

the Wald statistic -computed as \((\frac{B}{SE})^2\)- which follows a chi-square distribution;

the degrees of freedom for the Wald statistic;

the degrees of freedom for the Wald statistic;

the significance levels for the b-coefficients;

the significance levels for the b-coefficients;

exponentiated b-coefficients or \(e^B\) are the odds ratios associated with changes in predictor scores;

exponentiated b-coefficients or \(e^B\) are the odds ratios associated with changes in predictor scores;

the 95% confidence interval for the exponentiated b-coefficients.

the 95% confidence interval for the exponentiated b-coefficients.

The b-coefficients complete our logistic regression model, which is now

$$P(death_i) = \frac{1}{1 + e^{\,-\,(-9.079\,+\,0.124\, \cdot\, age_i)}}$$

For a 75-year-old client, the probability of passing away within 5 years is

$$P(death_i) = \frac{1}{1 + e^{\,-\,(-9.079\,+\,0.124\, \cdot\, 75)}}=$$

$$P(death_i) = \frac{1}{1 + e^{\,-\,0.249}}=$$

$$P(death_i) = \frac{1}{1 + 0.780}=$$

$$P(death_i) \approx 0.562$$

So now we know how to predict death within 5 years given somebody’s age. But how good is this prediction? There's several approaches. Let's start off with model comparisons.

Logistic Regression - Baseline Model

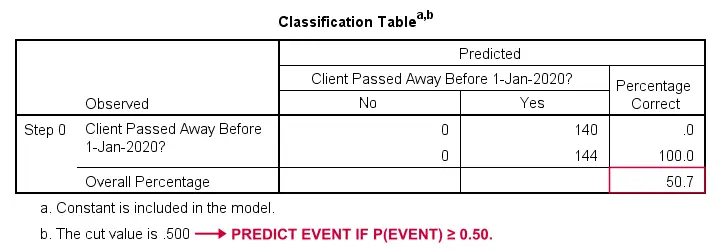

How could we predict who passed away if we didn't have any other information? Well, 50.7% of our sample passed away. So the predicted probability would simply be 0.507 for everybody.

For classification purposes, we usually predict that an event occurs if p(event) ≥ 0.50. Since p(died) = 0.507 for everybody, we simply predict that everybody passed away. This prediction is correct for the 50.7% of our sample that died.

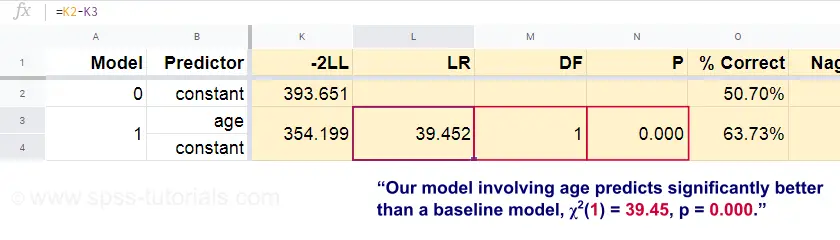

Logistic Regression - Likelihood Ratio

Now, from these predicted probabilities and the observed outcomes we can compute our badness-of-fit measure: -2LL = 393.65. Our actual model -predicting death from age- comes up with -2LL = 354.20. The difference between these numbers is known as the likelihood ratio \(LR\):

$$LR = (-2LL_{baseline}) - (-2LL_{model})$$

Importantly, \(LR\) follows a chi-square distribution with \(df\) degrees of freedom, computed as

$$df = k_{model} - k_{baseline}$$

where \(k\) denotes the numbers of parameters estimated by the models. As shown in this Googlesheet, \(LR\) and \(df\) result in a significance level for the entire model.

The null hypothesis here is that some model predicts equally poorly as the baseline model in some population. Since p = 0.000, we reject this: our model (predicting death from age) performs significantly better than a baseline model without any predictors.

But precisely how much better? This is answered by its effect size.

Logistic Regression - Model Effect Size

A good way to evaluate how well our model performs is from an effect size measure. One option is the Cox & Snell R2 or \(R^2_{CS}\) computed as

$$R^2_{CS} = 1 - e^{\frac{(-2LL_{model})\,-\,(-2LL_{baseline})}{n}}$$

Sadly, \(R^2_{CS}\) never reaches its theoretical maximum of 1. Therefore, an adjusted version known as Nagelkerke R2 or \(R^2_{N}\) is often preferred:

$$R^2_{N} = \frac{R^2_{CS}}{1 - e^{-\frac{-2LL_{baseline}}{n}}}$$

For our example data, \(R^2_{CS}\) = 0.130 which indicates a medium effect size. \(R^2_{N}\) = 0.173, slightly larger than medium.

Last, \(R^2_{CS}\) and \(R^2_{N}\) are technically completely different from r-square as computed in linear regression. However, they do attempt to fulfill the same role. Both measures are therefore known as pseudo r-square measures.

Logistic Regression - Predictor Effect Size

Oddly, very few textbooks mention any effect size for individual predictors. Perhaps that's because these are completely absent from SPSS. The reason we do need them is that

b-coeffients depend on the (arbitrary) scales of our predictors:

if we'd enter age in days instead of years, its b-coeffient would shrink tremendously. This obviously renders b-coefficients unsuitable for comparing predictors within or across different models.

JASP includes partially standardized b-coefficients: quantitative predictors -but not the outcome variable- are entered as z-scores as shown below.

Logistic Regression Assumptions

Logistic regression analysis requires the following assumptions:

- independent observations;

- correct model specification;

- errorless measurement of outcome variable and all predictors;

- linearity: each predictor is related linearly to \(e^B\) (the odds ratio).

Assumption 4 is somewhat disputable and omitted by many textbooks1,6. It can be evaluated with the Box-Tidwell test as discussed by Field4. This basically comes down to testing if there's any interaction effects between each predictor and its natural logarithm or \(LN\).

Multiple Logistic Regression

Thus far, our discussion was limited to simple logistic regression which uses only one predictor. The model is easily extended with additional predictors, resulting in multiple logistic regression:

$$P(Y_i) = \frac{1}{1 + e^{\,-\,(b_0\,+\,b_1X_{1i}+\,b_2X_{2i}+\,...+\,b_kX_{ki})}}$$

where

- \(P(Y_i)\) is the predicted probability that \(Y\) is true for case \(i\);

- \(e\) is a mathematical constant of roughly 2.72;

- \(b_0\) is a constant estimated from the data;

- \(b_1\), \(b_2\), ... ,\(b_k\) are the b-coefficient for predictors 1, 2, ... ,\(k\);

- \(X_{1i}\), \(X_{2i}\), ... ,\(X_{ki}\) are observed scores on predictors \(X_1\), \(X_2\), ... ,\(X_k\) for case \(i\).

Multiple logistic regression often involves model selection and checking for multicollinearity. Other than that, it's a fairly straightforward extension of simple logistic regression.

Logistic Regression - Next Steps

This basic introduction was limited to the essentials of logistic regression. If you'd like to learn more, you may want to read up on some of the topics we omitted:

- odds ratios -computed as \(e^B\) in logistic regression- express how probabilities change depending on predictor scores ;

- the Box-Tidwell test examines if the relations between the aforementioned odds ratios and predictor scores are linear;

- the Hosmer and Lemeshow test is an alternative goodness-of-fit test for an entire logistic regression model.

Thanks for reading!

References

- Warner, R.M. (2013). Applied Statistics (2nd. Edition). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Agresti, A. & Franklin, C. (2014). Statistics. The Art & Science of Learning from Data. Essex: Pearson Education Limited.

- Hair, J.F., Black, W.C., Babin, B.J. et al (2006). Multivariate Data Analysis. New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall.

- Field, A. (2013). Discovering Statistics with IBM SPSS Statistics. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Howell, D.C. (2002). Statistical Methods for Psychology (5th ed.). Pacific Grove CA: Duxbury.

- Pituch, K.A. & Stevens, J.P. (2016). Applied Multivariate Statistics for the Social Sciences (6th. Edition). New York: Routledge.

SPSS TUTORIALS

SPSS TUTORIALS

THIS TUTORIAL HAS 24 COMMENTS:

By Ruben Geert van den Berg on February 12th, 2023

Hi Mike!

This is very probably due to a human error or inaccuracies.

Make sure you

-minimize rounding of all numbers involved

-compare the exact same models

-use the exact same variables

-treat missing values similarly as SPSS

and you should be able to replicate SPSS' results.

Hope that helps!

SPSS tutorials

By Donald W. Buckwalter on September 6th, 2023

Thanks! This is clearly written and presented--appropriate to my level of comprehension.

By Neal Bliven on October 25th, 2023

Nicely worded and logically presented.

By Shifat Shafin on April 11th, 2025

Thanks for this excellent way of step by step learning;