- SPSS Moderation Regression - Example Data

- SPSS Moderation Regression - Dialogs

- SPSS Moderation Regression - Coefficients Output

- Simple Slopes Analysis I - Fit Lines

- Simple Slopes Analysis II - Coefficients

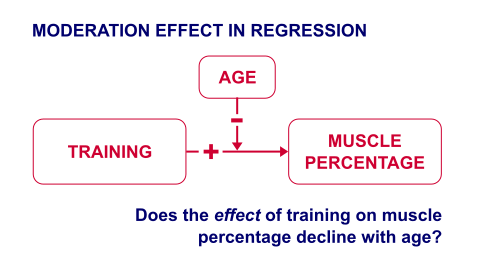

A sports doctor routinely measures the muscle percentages of his clients. He also asks them how many hours per week they typically spend on training. Our doctor suspects that clients who train more are also more muscled. Furthermore, he thinks that the effect of training on muscularity declines with age. In multiple regression analysis, this is known as a moderation interaction effect. The figure below illustrates it.

So how to test for such a moderation effect? Well, we usually do so in 3 steps:

- if both predictors are quantitative, we usually mean center them first;

- we then multiply the centered predictors into an interaction predictor variable;

- finally, we enter both mean centered predictors and the interaction predictor into a regression analysis.

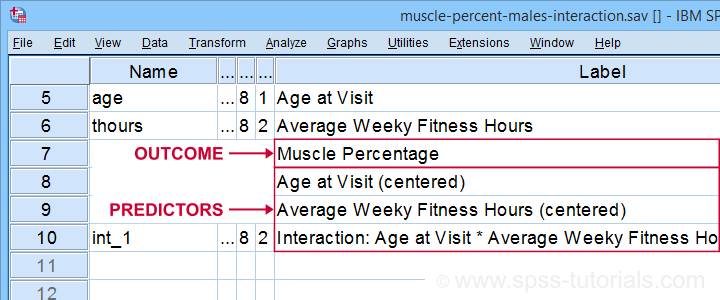

SPSS Moderation Regression - Example Data

These 3 predictors are all present in muscle-percent-males-interaction.sav, part of which is shown below.

We did the mean centering with a simple tool which is downloadable from SPSS Mean Centering and Interaction Tool.

Alternatively, mean centering manually is not too hard either and covered in How to Mean Center Predictors in SPSS?

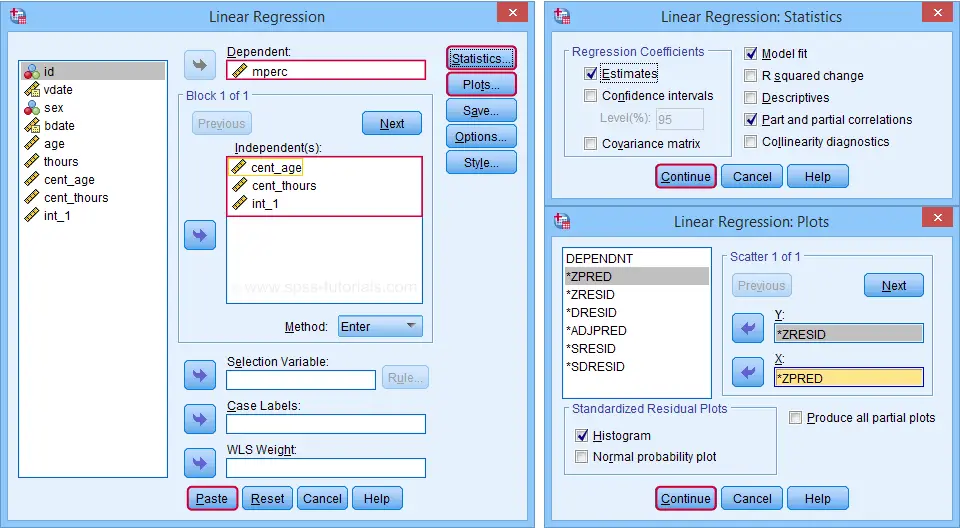

SPSS Moderation Regression - Dialogs

Our moderation regression is not different from any other multiple linear regression analysis: we navigate to

and fill out the dialogs as shown below.

and fill out the dialogs as shown below.

Clicking results in the following syntax. Let's run it.

REGRESSION

/MISSING LISTWISE

/STATISTICS COEFF OUTS R ANOVA ZPP

/CRITERIA=PIN(.05) POUT(.10)

/NOORIGIN

/DEPENDENT mperc

/METHOD=ENTER cent_age cent_thours int_1

/SCATTERPLOT=(*ZRESID ,*ZPRED)

/RESIDUALS HISTOGRAM(ZRESID).

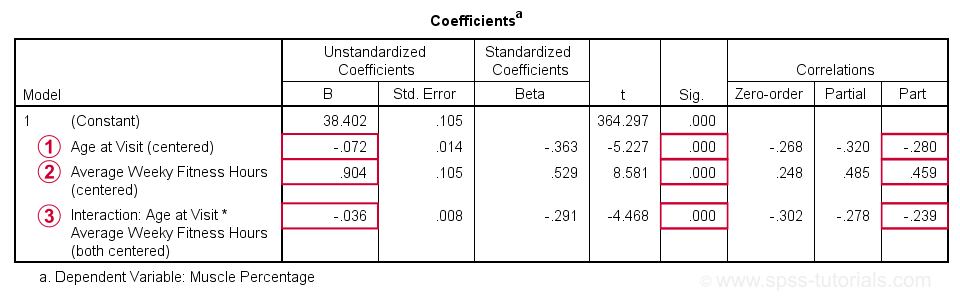

SPSS Moderation Regression - Coefficients Output

Age is negatively related to muscle percentage. On average, clients lose 0.072 percentage points per year.

Age is negatively related to muscle percentage. On average, clients lose 0.072 percentage points per year.

Training hours are positively related to muscle percentage: clients tend to gain 0.9 percentage points for each hour they work out per week.

Training hours are positively related to muscle percentage: clients tend to gain 0.9 percentage points for each hour they work out per week.

The negative B-coefficient for the interaction predictor indicates that the training effect becomes more negative -or less positive- with increasing ages.

The negative B-coefficient for the interaction predictor indicates that the training effect becomes more negative -or less positive- with increasing ages.

Now, for any effect to bear any importance, it must be statistically significant and have a reasonable effect size.

At p = 0.000, all 3 effects are highly statistically significant. As effect size measures we could use the semipartial correlations (denoted as “Part”) where

- r = 0.10 indicates a small effect;

- r = 0.30 indicates a medium effect;

- r = 0.50 indicates a large effect.

The training effect is almost large and the age and age by training interaction are almost medium. Regardless of statistical significance, I think the interaction may be ignored if its part correlation r < 0.10 or so but that's clearly not the case here. We'll therefore examine the interaction in-depth by means of a simple slopes analysis.

With regard to the residual plots (not shown here), note that

- the residual histogram doesn't look entirely normally distributed but -rather- bimodal. This somewhat depends on its bin width and doesn't look too alarming;

- the residual scatterplot doesn't show any signs of heteroscedasticity or curvilinearity. Altogether, these plots don't show clear violations of the regression assumptions.

Creating Age Groups

Our simple slopes analysis starts with creating age groups. I'll go for tertile groups: the youngest, intermediate and oldest 33.3% of the clients will make up my groups. This is an arbitrary choice: we may just as well create 2, 3, 4 or whatever number of groups. Equal group sizes are not mandatory either and perhaps even somewhat unusual. In any case, the syntax below creates the age tertile groups as a new variable in our data.

rank age

/ntiles(3) into agecat3.

*Label new variable and values.

variable labels agecat3 'Age Tertile Group'.

value labels agecat3 1 'Youngest Ages' 2 'Intermediary Ages' 3 'Highest Ages'.

*Check descriptive statistics age per age group.

means age by agecat3

/cells count min max mean stddev.

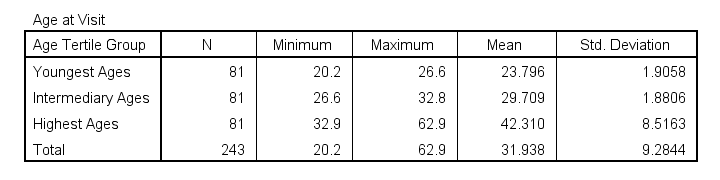

Result

Some basic conclusions from this table are that

- our age groups have precisely equal sample sizes of n = 81;

- the group mean ages are unevenly distributed: the difference between young and intermediary -some 6 years- is much smaller than between intermediary and highest -some 13 years;

- the highest age group has a much larger standard deviation than the other 2 groups.

Points 2 and 3 are caused by the skewness in age and argue against using tertile groups. However, I think that having equal group sizes easily outweighs both disadvantages.

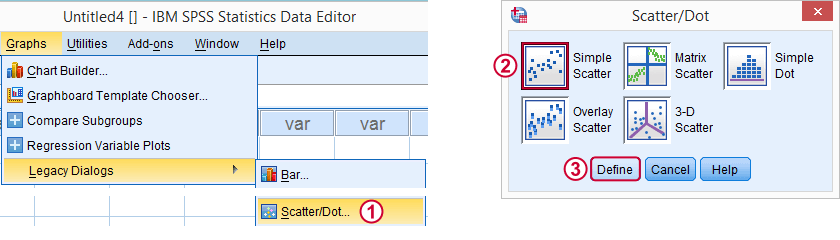

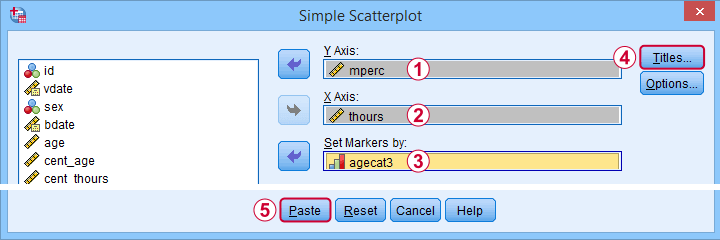

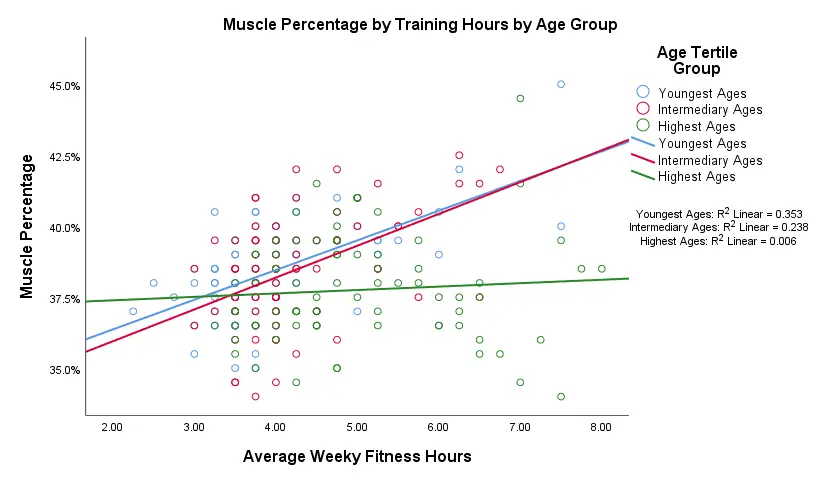

Simple Slopes Analysis I - Fit Lines

Let's now visualize the moderation interaction between age and training. We'll start off creating a scatterplot as shown below.

Clicking results in the syntax below.

GRAPH

/SCATTERPLOT(BIVAR)=thours WITH mperc BY agecat3

/MISSING=LISTWISE

/TITLE='Muscle Percentage by Training Hours by Age Group'.

*After running chart, add separate fit lines manually.

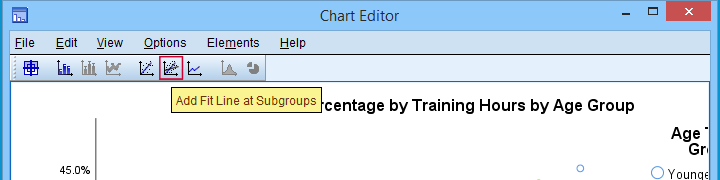

Adding Separate Fit Lines to Scatterplot

After creating our scatterplot, we'll edit it by double-clicking it. In the Chart Editor window that opens, we click the icon labeled Add Fit Line at Subgroups

After adding the fit lines, we'll simply close the chart editor. Minor note: scatterplots with (separate) fit lines can be created in one go from the Chart Builder in SPSS version 25+ but we'll cover that some other time.

Result

Our fit lines nicely explain the nature of our age by training interaction effect:

- the 2 youngest age groups show a steady increase in muscle percentage by training hours;

- for the oldest clients, however, training seems to hardly affect muscle percentage. This is how the effect of training on muscle percentage is moderated by age;

- on average, the 3 lines increase. This is the main effect of training;

- overall, the fit line for the oldest group is lower than for the other 2 groups. This is our main effect of age.

Again, the similarity between the 2 youngest groups may be due to the skewness in ages: the mean ages for these groups aren't too different but very different from the highest age group.

Simple Slopes Analysis II - Coefficients

After visualizing our interaction effect, let's now test it: we'll run a simple linear regression of training on muscle percentage for our 3 age groups separately. A nice way for doing so in SPSS is by using SPLIT FILE.

The REGRESSION syntax was created from the menu as previously but with (uncentered) training as the only predictor.

sort cases by agecat3.

split file layered by agecat3.

*Run simple linear regression with uncentered training hours on muscle percentage.

REGRESSION

/MISSING LISTWISE

/STATISTICS COEFF OUTS R ANOVA ZPP

/CRITERIA=PIN(.05) POUT(.10)

/NOORIGIN

/DEPENDENT mperc

/METHOD=ENTER thours

/SCATTERPLOT=(*ZRESID ,*ZPRED)

/RESIDUALS HISTOGRAM(ZRESID).

*Split file off.

split file off.

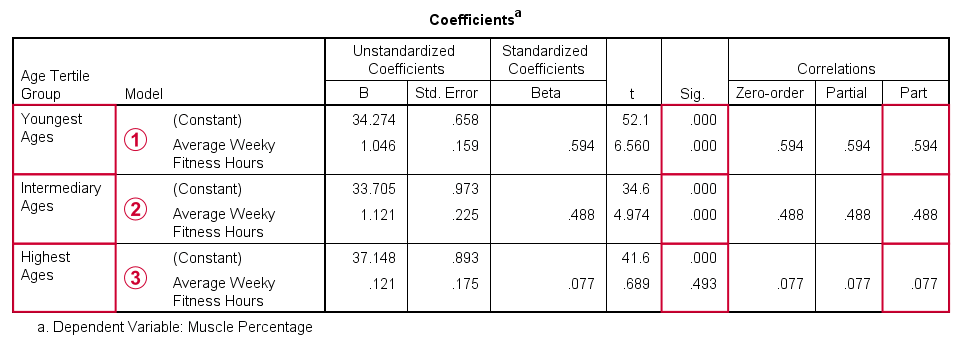

Result

The coefficients table confirms our previous results:

for the youngest age group, the training effect is statistically significant at p = 0.000. Moreover, its part correlation of r = 0.59 indicates a large effect;

for the youngest age group, the training effect is statistically significant at p = 0.000. Moreover, its part correlation of r = 0.59 indicates a large effect;

the results for the intermediary age group are roughly similar to the youngest group;

the results for the intermediary age group are roughly similar to the youngest group;

for the highest age group, the part correlation of r = 0.077 is not substantial. We wouldn't take it seriously even if it had been statistically significant -which it isn't at p = 0.49.

for the highest age group, the part correlation of r = 0.077 is not substantial. We wouldn't take it seriously even if it had been statistically significant -which it isn't at p = 0.49.

Last, the residual histograms (not shown here) don't show anything unusual. The residual scatterplot for the oldest age group looks curvilinear except from some outliers. We should perhaps take a closer look at this analysis but we'll leave that for another day.

Thanks for reading!

SPSS TUTORIALS

SPSS TUTORIALS

THIS TUTORIAL HAS 9 COMMENTS:

By Ruben Geert van den Berg on November 8th, 2022

Hi Jon!

I was completely unaware of the /METHOD TEST... procedure but is sounds useful.

I quite often run hierarchical regression by using multiple /METHOD ENTER ... subcommands but I always find it a bit of a struggle to decide on the order of such sets of predictors.

/METHOD TEST... sounds like a possible solution for this.

P.s. I find the REGRESSION dialog rather incomplete. Why doesn't it include subdialogs for A) interaction effects and B) categorical variables like the logistic regression dialogs?

And concerning the latter: I think it's not optimal that LOGISTIC REGRESSION does not have an option to mean center predictors prior to computing interactions. It simply uses the products of raw scores, which is rarely what we want.

And if I may add a quick question: how do you feel about mean centering dichotomous variables (0-1 coded) either for interactions with quantitative or other dichotomous variables?

The standard literature suggests these should never be mean centered but doing so sometimes seems to alleviate colinearity in real-life analyses.

By Jon K Peck on November 8th, 2022

Your comments on the regression dialog box make sense. That dialog, although still heavily used, is very old and could definitely use some improvement. You can, of course, easily standardize variables via Descriptives, and even without that, the output includes standardized coefficients (pace interactions).

As you know, though, standardizing does not affect inference - it just makes interpreting the interaction terms more convenient, so I don't bother unless I need to address that issue.

As for dichotomies, standardizing or just mean centering, of course, puts the evaluation point at a value that isn't meaningful. Andrew Gelman says this:

For comparing coefficients for different predictors within a model, standardizing gets the nod. (Although I don’t standardize binary inputs. I code them as 0/1, and then I standardize all other numeric inputs by dividing by two standard deviation, thus putting them on approximately the same scale as 0/1 variables.)

For comparing coefficients for the same predictors across different data sets, it’s better not to standardize–or, to standardize only once.

By Hana on April 18th, 2024

Thanks for this great tutorial! How would I get the simple slopes coefficients if my model has covariates?

By Ruben Geert van den Berg on April 18th, 2024

Hi Hana!

For the coefficients table, just enter the exact same covariates as for the main analysis with the interaction predictor.

The simple slopes chart, however, is complicated in this case. Technically, you could run it on the residuals from a regression with only the covariates (with SPLIT FILE in effect).

Hope that helps!

Ruben

SPSS tutorials